Purpose of this step: to identify all investors who can actually invest in you.

This first step of raising VC funding is the most important one. Once you actually know which VCs are really the relevant ones to talk to, you minimze wasting your time on irrelevant interactions and can focus all your energy on those VCs that are real prospects.

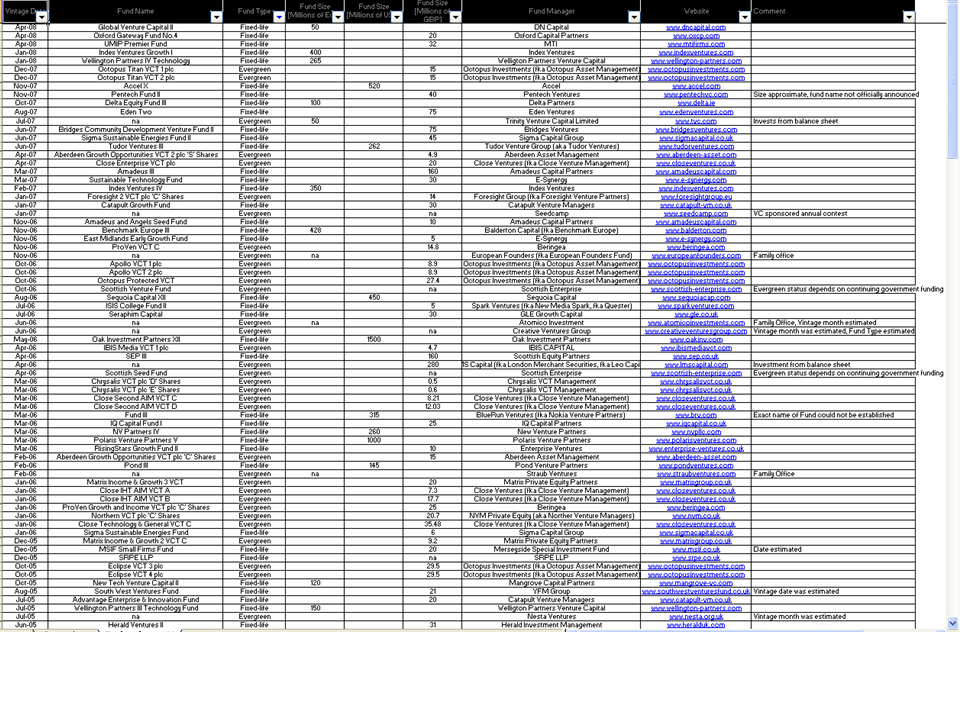

Update: I have started building a public list of VC funds. You can view them here: http://creator.zoho.com/jenslapinski/list-of-vc-funds I will build out this list until it contains all active VC funds operating in the UK. If you help me, I think we could broaden its coverage very quickly.

Steps for qualifying a VC as a prospective investor

1) Create a long list of all VC firms that you can find that have made investments in the past 24 months

2) Identify those VCs that match you industry sector and your geographic location

3) Identify VCs that have invested in competing companies

4) Identify those VCs that have money to invest in a company like yours

1) Create a long list of VC firms

The best way to find a list of all the active investors is to approach a company that tracks VC deals. There are Library House (where I used to work), VentureOne, VentureXpert, Initiative Europe and many more.

These companies will be able to give you a list of all VC firms that have actually made deals in the last 24 months. A VC that has not made an investment in the past 24 months is an unlikely candidate to approach. Exceptions are newly-formed partnerships that are yet to make their first investment, these should be very high up on your list.

I really suggest you try to get access to such a deal list, it will help you reduce a lot of work later on. If you really can’t get access, then you will have to do with publicly available directores. You can find various on the web.

2) Identify VCs that match you industry sector and your geographic location

By visiting a VCs website, you will be able to see what industries a VC is actually investing in and where their offices are located. Remove all VCs from the long list that do not invest in your industry sector. They are completely irrelevant to you.

Move all VCs who do not have an office near you (near for a seed stage company means no further than a two hour drive) to a B list. As a rule of thumb, the more later stage you are (this means you have raised previous VC rounds or you are already generating revenue or are profitable) the further away a VC can be. VCs hardly ever invest in countries where they do not have an office. Unless you really know what you are doing, don’t approch a VC who is not in you country, unless you are happy to move to a city where they have an office. Move all these VCs to a B list.

3) Identify VCs that have invested in competing companies

When you are on the web sites of the VC firms, check out whether they have current portfolio companies (from which they haven’t divested, yet) that are competitors. As a rule of thumb, do not approach any of these VCs, move them to a C list. There are two reasons for this.

First: many VCs don’t invest in competing companies, all sorts of problems can arise as a consequence

Second: there are VCs that will give all your documentation to their portfolio companies, if they think it helps them. You would not really want that to happen…

4) Identify VCs that have money to invest

I have seen a lot of people waste a lot of time pitching to VCs who simply could not invest in them. This is the best way to waste a huge amount of time.

There are two reasons why a VC may not be able to invest in a company:

a) The VC has no money to invest

b) The company is asking for an amount of money that is incompatible with the fund that a VC has

In order to be able to assess the situation, it is extremely important that you know the following about the last fund that the VC has raised:

– What exactly is the vintage date (aka ‘first close’) of that fund?

– How large is the last fund?

| Quick background on VCs

In order to understand the importance of the last fund’s vintage date and size, it helps to understand how VCs work. Venture capital firms (VCs) are fund management companies that manage funds. The fund management company will typically manage several funds. Each individual fund is typically structured as a partnership. The partnership consists of two types of partners. General Partners (GPs) and Limited Partners (LPs). The GPs are the individuals working at the fund management company (these are the ‘VCs’ you will meet and whom you can see on the website). The LPs can be either institutions (pensions funds, fund of funds, banks, insurance companies, operating companies, universities, etc) or rich individuals that have invested their money in the specific fund in question. The GPs are responsible for investing the money in start-up companies.The most important thing to understand is that there are two types of funds: Fixed terms funds, and open-ended funds (also called evergreen funds). A typical VC fund will be a fixed terms fund. The typical running time will be 10 years. This means that the VCs will have a first close of their fund (sometimes referred to as the ‘vintage year’ and ‘vintage month’ of the fund). Once the VCs have the money in the bank, they can actually start investing.The typical investment pattern of the Fund will look like this (from vintage date forward). VCs are usually bound by their Fund agreements to invest 60% of the Fund in the first four years of the fund’s life time. What they don’t invest, they have to give back (as a rule of thumb). They must then invest the remainder in years 5-7, but they are contractually prohibited to invest in companies they are not already invested in. As a generalization, the overall contractual agreement will look like this:Years 1-4: invest in new start-upsYears 5-7: invest only in existing portfolio companiesYears 8-10: no further investments Here is a rule of thumb of what kind of companies VCs will invest in, based on the latest fund that they have raised: Year 1: Seed stage and later Year 2: Series A and later Year 3: Series B and later Year 4: Series C and later Year 5+: no investments in non-portfolio companies When a VC with a fixed term fund sells their holding in a company, typically all of the money is handed to the investors in the fund. It does not get recycled into new investments. Evergreen funds by contrast operate differently. These funds will recycle back to the fund a good proportion of their money that is generated when a portfolio company is sold. These funds will either have money to invest when they are new (similar to fixed term funds) or when they had had a large ‘exit’ (exit means selling a portfolio company). The second important aspect is to understand what impact the size of the fund has. The size of a fund will determine what kind of companies a fund will invest in. Not in terms of what stage they are in, but the total capital requirements of that company. What this means is as follows. Imagine there is a VC with a $50m fund. The VC will have a contractual obligation to invest no more than 10% of the fund in a company. That would be $5m. If you are asking for a $5m Series A round, the VC could not invest, as there would be no opportunity to place money in any eventual follow-on round. In this case, your capital requirements are too large for this particular fund. A second example might be a VC firm with a $1bn fund. This means the VC is looking to place at least $25m per portfolio company. If you went to this VC with a company that has a total capital requirement of $10m, they would simply not be interested. Your company’s capital requirements are too small for them. |

So, for each VC firm that is on your list, you should figure out both the vintage date and the size of their last fund. Then compare that with your own situation. Remove all firms that have funds that are too old for your stage. Remove all firms that have funds that are either too large or too small for you.

There are three ways of figuring out what the last fund was:

– ask the VC (be specific, as for the date of the first close of the last fund), many VC firms will be press releases on their websites that will give you an idea of what the last fund was.

– Google for the name of the VC and ‘fund’ and ‘first close’ and you will find some press stories that are not on the website.

– There are some very expensive databases (e.g. VentureXpert) that you can buy that will tell you the vintage date and size.

In April 2008, I created a little list of all VC funds (that I could find) that invest in IT/Internet companies based in the UK. A screenshot of this listis included below. I only include this list as an illustration of the kind of information you should collect for yourself:

(Comment on the list abvove: I have probably missed a few funds: mea culpa!)

Once you have a fund list like the one I show above, you will find it very easy to identify the VC firms that you should approach.

Final comment

When you ask a VC whether they have money to invest in your company they will always say yes when they think your company will eventually get funded by somebody (provided they invest in your country and industry). They will always want you to send them the executive summary and/or to come and pitch, even when they have no personal interest in you and/or can’t invest in you.

There are two reasons for this. First, a VC wants to be ‘in the deal flow’, so they can see what is going on. This keeps them informed on the sector. The second reason is that a VC wants to and needs to be seen to be in the deal flow. This is important, because their co-partners and other investors need to see them as being in the deal flow. No less important is that VCs often report back to their LPs what percentage of companies that got funded they actually saw before the deal. If a VC firm sees most of the deals that got done, this means they were in the deal flow and it is important for LPs to know that their GPs actually see what is going on.

What this means is that when a VC wants to see you pitch, this does not mean they actually have an interest in investing in you, nor does it mean that they can invest in you. They might just let you pitch, so they are in the deal flow. This is fine, you can use these VCs to practice your pitch.

I will tackle how to approach each fund and how to practice your pitch in a separate post (Part 3 of this series).

![]()

![]() Subscribe in a Reader

Subscribe in a Reader ![]() Subscribe by Email

Subscribe by Email

Related articles

- Implications Of How A VC Is Funded: Family Office [via Zemanta]

- Implications Of How A VC Is Funded: Diverse Limited Partners [via Zemanta]

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)